Maritime shipping giant CMA CGM’s Xavier Leclercq plots the course towards carbon-neutrality by 2050

When it comes to integrating the latest decarbonization technology into the world’s maritime fleet, Xavier Leclercq doesn’t hesitate: “Implement, measure, learn and improve”. It’s a lesson he’s learned from his experience with LNG, but can it be applied to green methanol and green ammonia? As Vice President of CMASHIPS for the CMA CGM Group, which operates close to 600 vessels, Leclercq has a birds’-eye view of the challenges and the opportunities involved in scaling up low- and zero-emission fuels.

By Daniel Whitaker

Discover: Xavier Leclercq, what have been the biggest challenges facing the shipping industry in the last five years?

Xavier Leclercq: Well, in the last five years the biggest challenge the shipping industry has had to face is environmental – and we’ve seen the pace of new rules around this challenge increase significantly at national, European and international levels. For example, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) 2023 regulations introduced a ratings systems to reduce a ship’s carbon intensity, and the EU’s Fit for 55 regulation proposes a carbon tax.

We need strong partners. The challenge can’t be solved alone.

How much of a difference are the IMO 2023 and EU Fit for 55 regulations making?

That’s not an easy question to answer. First, there’s a big difference between the IMO 2023 and the EU Fit for 55 regulations. If I look at the IMO, at the moment it’s basically a strong recommendation, but there are no penalties involved yet. There’s still a financial impact because ship owners will have to adapt their fleets and reporting systems. The EU Fit for 55, however, will have a direct impact on transportation costs, which is significant, and a big driver for change.

What do you think of the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasting only a 6 percent annual decline in shipping’s carbon emissions through to 2050, which would miss greenhouse gas reduction targets?

I think everyone has acknowledged that the IMO’s objectives [40 percent reduction in carbon intensity by 2030] are a challenge, and right now neither the technologies nor the supply chain for low-emission fuels are in place. There are some organizations trying to address the challenge, but it isn’t solved yet. So, yes, we can have some pessimistic forecasts, but I’m quite optimistic.

.jpg?sfvrsn=b4b6b7b9_4)

Can you give us an approximiate idea of the investment involved?

Well, I know the investment CMA CGM has made over the last five years because we’ve anticipated the constrainsts and our ambitious is to lead the battle. I’d say we’re talking about $100 billion of overall investments for the shipping industry. There are some 90,000 ships sailing over the world, and at some point the whole fleet will have to be replaced.

I suppose it isn’t helpful that the current market seems extremely volatile. What differences does that make?

The truth is we’ve been living for years with an extremely low cost of transportation. For decades, the cost of an iPhone, which was carried from China to the United States, was only a few cents. So, that will be part of the change too: If we want to solve the environmental challenge, transport costs won’t stay the same.

Is there a particular solution CMA CGM is targeting?

No, we don’t think there’ll be one single solution, it’ll be a combination of solutions. Our strategy is simple: As soon as a technology reaches a certain stage of development, we’ll test it and implement it. We did that with liquefied natural gas (LNG). We were the second to use methanol. We’re testing carbon capture. And we’re making progress with ammonia. When that’s near ready, we’ll implement it in the fleet.

What role do partnerships play?

Partnerships play a key role – we can’t do anything alone. The challenge is so big that we need a large network and strong partners – and of course, MAN Energy Solutions is one of them. Shipyards are also partners. And we collaborate with classification societies and some of our competitors, sharing, for example, information regarding technical solutions. We need strong partners. The challenge can’t be solved alone.

Is it important to be a first mover with these technologies despite remaining challenges?

Yes. You need to impletment the technology into real-world conditions, measure it and learn from it before you can improve it. Take LNG as an example – we knew we had an issue with the methane slip, but since we were the first to implement it we’ve also gained a lot of experience. We measured during construction and explotations phases, we know exactly where we stand, what potential solutions we have, and we’re closing to bringing out a fourth version that will reduce the methane slip by as much as 70 percent. The process should be the same with any other technology: implement, measure, learn and improve.

Since we’re talking about LNG, does it have advantages or disadvantages over green methanol?

Well, it’s easy to handle, it’s been known for decades, and it’s available – which isn’t the case for green methanol yet. When we started the project, we only had one bunkering station in Rotterdam. Now, we can bunker in Singapore, in Japan, in the United States. The application on container ships is of course different, but in the last four years we’ve been learning a lot and feel at ease using LNG. And if we solve the methane slip – I think a 90-percent reduction is possible – then LNG will be a good transition fuel for some time, especially knowing we can use biomethanes and are compatible with e-methane once its ready.

How long do you think LNG can maintain a lead over green methanol?

We learned with LNG that developing a supply chain for a new fuel takes time and investment. So, I imagine it’ll take a minimum of ten years to get the amount of green methanol required just for the vessels on order. The good thing though is that when you have a client saying, “Hey, I need a million tonnes”, then of course the industry will follow – you’re sending a clear signal to the energy industry and you can pursue collaborations. That was the case with LNG, where we jointly built the project with TotalEnergies, and it will be the same story with green methanol. We already have 24 methanol-ready ships, and the energy suppliers understand there’s a real demand. It’ll take time, but the pace is improving.

Given the long life of ships, how can ship owner’s deal with the uncertainty about which fuel is going to be the best in the future?

Many shipyards are already saying they’re methanol and ammonia ready. And we need to undertand that an LNG-powered vessel or a methanol-powered vessels use dual fuel engines, so they have flexibility.

What about green hydrogen? You’ve called it ‘the greatest challenge for the shipping industry - is storage the biggest obstacle?

Well, it’s one of them. Storing liquid hydrogen at -251° Celsius – just a few degrees from absolute zero – is quite a challenge. But I don’t think it’s the only one. Prediction and transportation of hydrogen are also challenges. And producing hydrogen is costly in terms of energy, so the efficiency of the whole chain is quite trivial. I don’t think hydrogen will be a solution for the long haul. It can be a solution for short sea passages, land transportation, but for the amount of energy we need on our ships, it’s extremely challenging.

So, it will only be a part of the solution then. Do you think that major ports are going to be hubs for hydrogen and ammonia production or both?

It’s a bit like a car gas station. Ports will have to adapt to the different needs of their customers. At a gas station you can have diesel, you can have ethanol, you can have normal gas – it’ll be the same for ports. They’ll need to think about their investments, being able to provide the different fuels to ship owners, and build those facilities. For hydrogen, again, I think this will be mostly reserved to stowage, barges, and so on, not on the long haul. It will be very difficult to have this energy used for long distance.

One difference with shipping compared to land vehicles is the importance of retrofitting – with insufficient retrofitting and long vessel life driving low emission reductions in the IEA forecast. How do you see the opportunity for retrofitting?

We’ve been doing this for almost 20 years. We have an annual program to improve fleet efficiency – fitting bulbous bows to reduce ship resistance and save fuel, jumboizing ships to increase capacity, adding windshields or air lubricating systems for energy efficieny. Now, retrofitting to a different energy is a different story. Because of the tank, an LNG retrofit is costly. A methanol retrofit would be a far better option to upgrade the fleet. For ammonia, I don’t have the picture yet but any retrofit will have to include safety measures which might make it more difficult than methanol. Beyond that, retrofitting for efficiency should be a permanent questions and part of the daily work. We could reach a 20 percent reduction just be using the optimization and consumption reduction technologies that already exist. Is that being done sufficiently enough over the world? Well, that’s a good question. We can certainly get there.

About the author

Daniel Whitaker, based in London, is an economist and journalist who has been following trends in the energy transition for years. His work has appeared in a number of media outlets, including the Financial Times and The Economist.

Explore more topics

-

Hoegh - LNG-powered car carrier

With its first LNG-powered car carrier, Höegh Autoliners is taking a big step towards its target of net-zero by 2040. The centerpiece of the vessel is a MAN Energy Solutions MAN B&W ME-GI dual-fuel engine.

-

Maersk Halifax Retrofit

The world’s first methanol retrofit of the Very Large Container Vessel Maersk Halifax opens the doors for green fuels.

-

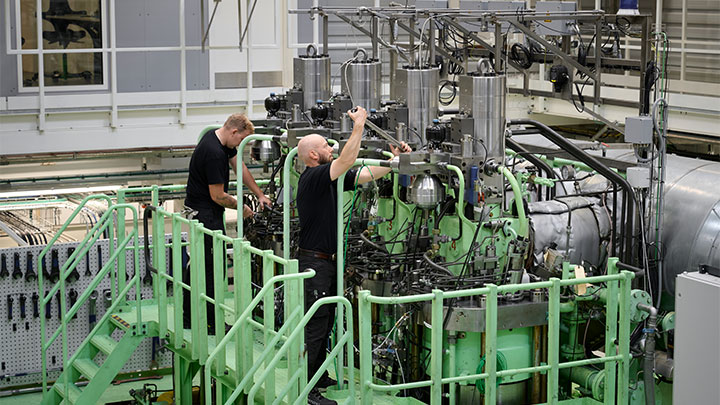

Methanol dual fuel retrofit

Engineers are now testing a retrofit for four-stroke ship engines that will enable ferry and cruise ship operators to meet the growing requirements on emission reduction with green methanol.

MAN Energy Solutions is now Everllence.

We have adopted a new brand name and moved to a new domain: www.everllence.com. This page will also be relocated there shortly. We are working on shifting all pages to www.everllence.com.